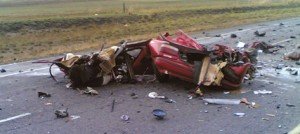

Despite huge investment having been made towards improvement of road infrastructure in the country, road traffic fatalities have been on the rise. The worst victims are the Vulnerable Road Users. The approach towards road safety has to change, says A P Bahadur, PPP expert for Asian Development Bank, Haryana.

Despite huge investment having been made towards improvement of road infrastructure in the country, road traffic fatalities have been on the rise. The worst victims are the Vulnerable Road Users. The approach towards road safety has to change, says A P Bahadur, PPP expert for Asian Development Bank, Haryana.

India has now achieved the dubious distinction of having the highest number of road fatalities amongst the countries in transition. National Crime Record Bureau Report records that around 1,27,000 persons were killed during 2009 while travelling by various modes of transport on Indian roads, implying one death on roads every 4.5 minutes. Kopits and Cropper (Kopits and Cropper, 2005) used the experience of 88 countries to model the dependence of the total number of fatalities on fatality rates per unit vehicle, vehicles per unit population, and per-capita income of the society. Their projections of future traffic fatalities suggest that the global road death toll will grow by approximately 66% over the next twenty years with increase in fatalities of almost 92% in China and 147% in India. As against this, there will be a decline of approximately 28% in high-income countries. This implies that road fatalities in India would reach a total of about 1,98,000 in 2042, before starting (perhaps) to decline.

India has now achieved the dubious distinction of having the highest number of road fatalities amongst the countries in transition. National Crime Record Bureau Report records that around 1,27,000 persons were killed during 2009 while travelling by various modes of transport on Indian roads, implying one death on roads every 4.5 minutes. Kopits and Cropper (Kopits and Cropper, 2005) used the experience of 88 countries to model the dependence of the total number of fatalities on fatality rates per unit vehicle, vehicles per unit population, and per-capita income of the society. Their projections of future traffic fatalities suggest that the global road death toll will grow by approximately 66% over the next twenty years with increase in fatalities of almost 92% in China and 147% in India. As against this, there will be a decline of approximately 28% in high-income countries. This implies that road fatalities in India would reach a total of about 1,98,000 in 2042, before starting (perhaps) to decline.

In the past few years, traffic fatalities have grown at around 7.5% per year. Table 1 shows the growth of RTCs, RTIs, fatalities and number of vehicle for the period between 2005 and 2009.

Even if it is presumed that road fatalities would start declining henceforth and that the present growth per year would decline in a linear manner to 0% by 2030, about 2,60,000 fatalities can be expected by the year 2030 (Dinesh Mohan, Omer Tsimhoni, Michael Sivak, Michael J Flannagan, The University of Michigan, 2009). Besides fatalities, road traffic crashes are important causes of disability and it is estimated that two million people have disabilities that result from road traffic crashes in India.

Although road traffic crashes clearly have a health impact on individuals and society, traffic safety is often considered a transportation concern rather than a public health problem. This attitude has to change in India. Road safety is now a public health issue as also recognised by World Health Organisation (WHO).

| Year |

RTCs (in thousands) |

% Variation over previous year |

RTIs (in thousands) |

% Variation over previous year |

Fatalities In nos. |

% Variation over previous year |

No. of Vehicles (in thousands) |

| 2005 | 390.4 | 8.0 | 447.9 | 8.2 | 98.254 | 7.5 | 66,289 |

| 2006 | 394.4 | 1.0 | 452.9 | 1.1 | 1.05,725 | 7.6 | 72,718* |

| 2007 | 418.6 | 6.1 | 465.3 | 2.7 | 1,14,590 | 8.4 | 72,718* |

| 2008 | 415.8 | -0.7 | 469.1 | 0.8 | 1,18,239 | 3.2 | 89,618* |

| 2009 | 421.6 | 1.4 | 466.6 | -0.5 | 1,26,896 | 7.3 | 89,6188* |

Road traffic crashes translate to an annual loss of about 3% of GDP. The irony of the situation is that the country has embarked upon a massive programme for development of roads at national, state and local level. The total investment on National Highways Development Project (for improvement of National Highways), Prime Minister Gramin Sadak Yojna (for improving accessibility to villages) and JNNRUM (for development of urban roads) is going to be around `5,10,000 crore or even more when completed. But road fatalities have increased from 98,254 in the year 2005 to 1,27,000 in 2009. This clearly shows that the investments are not giving the desired returns specially in improving road safety. The country is losing the main instrument of progress. Even if humanitarian considerations are ignored, there is a strong case for reducing road traffic crashes on purely economic ground as they consume massive financial resources that the country can ill afford to loose.

Despite huge investment having been made in the improvement of road infrastructure in the last decade, the road fatalities have increased at a much higher rate than that of RTCs and RTIs (Table 1). This clearly shows that the road infrastructure being provided is unsafe and the system of its planning, design, operation and management is devoid of the safety approach. The main reasons for high road traffic crashes, injuries and fatalities can be identified as below:

- Lack of commitment and insensitivity towards criticality of safety on roads amongst policy makers, planners, road authorities, designers, developers, operators and users

- Tendency of quick results (short term view) on lowest initial investment

- Inadequate and improper safety provisions for VRUs (Vulnerable Road Users) on high speed roads where impacts are more severe

- Standards not entirely incorporating the systems approach in design, construction and operation of road network – thereby requiring critical review and modification

- Stage development approach

- Disregard / compromise on standards by way of cost cutting

- Lack of planning and design for all categories of road users

- Absence of ‘life cycle costing approach’ to save on initial cost

- Piecemeal approach rather than holistic systems approach

- Incident based response instead of pro-active approach in road design and operation

- Belief that human error is the major cause of road traffic crashes

- More cars with capacity to be driven at high speeds but with less in-vehicle safety features

- Ineffective trauma care system

Since most of the development of National Highways and many State Highways is being done through Public Private Partnership (PPP) mode, it is important to know why safety has become a casualty in the development process.

• The approach being pushed for the development of roads through PPP is to keep the scope of development and improvement such that required investment is low and the project becomes viable for private investment on PPP. The first casualty in this approach obviously is on safety aspects. With this mindset of cost cutting, unsafe roads are being planned, designed, constructed and operated – specially the four/six lane highways. The safety aspect on four or six lane highway increases manifold compared to a two lane highway since those highways are meant for high speeds, and absence of safety features (for example segregation of local slow traffic and safety measures for VRUs), is a sure recipe for increase in traffic crashes and fatalities. Highway professionals are also being accused of ‘over engineering’ the project, whereas the fact is that roads in India are highly ‘under engineered’ (to borrow that term) and that is why they are unsafe. Sadly, the profession has failed to rise to the needs of the time – not succumbing to the pressures of keeping the cost low and by not compromising on safety.

- Almost all the developers still operate as contractors, on the principle of maximising the profits, thereby ignoring the safety requirements. The obligations of ‘corporate social responsibility’ also appear to have been ignored by many. It is unfortunate that the exceptional opportunity the country had for planning, designing, building and operating safe highways when it undertook the gigantic road development programme (which included National Highways Development Project – NHDP, other highways and urban roads) has been allowed to slip by, owing to this short sightedness of cost cutting.

- It is important to note that the Model Concession Agreement (MCA) finalised for highways to be developed on the PPP model is faulty. Hence, it cannot address the safety issue. According to its clause 18, the Concessionaire has to comply with the safety requirements given in MCA’s Schedule L which itself is defective: it provides for the appointment of a ‘safety consultant’ for safety audit whereas it should be ‘safety auditor’. The difference here is that a safety consultant looks after all the aspects of safety and is not confined to safety audit alone.

- Also Para 5 of this Schedule provides for safety auditor to be appointed by the Authority ‘no later than 4 months prior to the expected Project Completion Date’ as safety measures during construction. This implies that no safety issue is required to be addressed, during construction period which may continue for around two years’ period. The biggest problem is that Para 7 prescribes that all costs and expenses would be met out of a dedicated safety fund to be funded, owned and operated by the Authority or a substitute thereof whereas Article 16.3.2 prescribes another mechanism for safety fund. These ambiguous and somewhat conflicting provisions lead to ineffective application. Safety Audit Reports and recommendations remain on the shelf without actual implementation.

The world over, divided carriageway highways have been found to be safer compared to undivided ones but in India, the results are quite contrary. The main reason could be that most of our National and State Highways were initially lower category roads passing through linear settlements (built up areas). Proper attention has not been paid towards separation/ segregation of local slow traffic and severance of people living along the highways while planning and designing them for upgradation to four lanes. This has led to increased traffic conflicts and crashes. This problem is going to get further compounded with the proposed six-laning of Highways. Control (full or partial) on access would be practically very difficult because again, the approach being adopted is fo

r retrofitting on the existing four-lane highways and for structuring viable projects. It is rather doubtful that the intended increased mobility would be achieved. On the contrary, it may lead to more traffic crashes or local population forcefully building speed breakers. The trend has already started. Delhi-Gurgaon highway is a typical example. Sadly, lessons are yet to be learnt.

TrafficInfraTech Magazine Linking People Places & Progress

TrafficInfraTech Magazine Linking People Places & Progress